Update:

This post and Part I have been edited and combined into a single essay. The full version can be found here.

—————————————

Part I of this essay was an overview of how models (and scientific inquiry in general) actually work.

Let’s have a quick recap of the key points:

- Explanations should be as simple as possible, but no simpler.

- We make sense of complex systems by building models.

- Models are built for specific objectives and incorporate assumptions.

- The usefulness of a model depends on the validity of those assumptions.

- We cannot modify our objectives without re-examining our assumptions.

- Models can never be verified (shown to be true), only confirmed (shown to be useful).

- Scientific theories are models.

In this section, I want to explore the role of science in the search for ultimate truth.

We need to recognise the limitations of science as a method of pursuing truth, and with our newly-acquired understanding of models I hope that it will be clearer what those limitations are.

.

Methodological naturalism and the limitations of scientific models

Science, as a collection of models (termed theories or hypotheses according to their level of confirmation), is built on a set of assumptions. These are broadly grouped under the philosophy of methodological naturalism, and could be summarised as:

- The world we observe actually exists and is consistent.

- We can use our reason and senses to explore it.

- The material world is all that there is.

So we must ask ourselves: how useful is naturalism as an assumption?

The general opinion amongst philosophers of science is that it is a useful simplification. That is not to say that it is true, only that it is useful. Steven Schafersman, a geologist and prominent advocate against Creationism, writes that:

“… science is not metaphysical and does not depend on the ultimate truth of any metaphysics for its success … but methodological naturalism must be adopted as a strategy or working hypothesis for science to succeed. We may therefore be agnostic about the ultimate truth of naturalism, but must nevertheless adopt it and investigate nature as if nature is all that there is.”

Philosopher of science Robert Pennock, also a prominent voice against Creationism (and Intelligent Design), is more explicit. In his 1997 paper for a conference on “Naturalism, Theism and the Scientific Enterprise”, he states that science “makes use of naturalism only in a heuristic, methodological manner.” He also argues against even the theoretical possibility of using scientific methodology to explore supernatural issues:

“Methodological naturalism itself … follows from reasonable evidential requirements in science, most importantly, that hypotheses be intersubjectively testable by reference to law-governed processes.”

Why does this preclude the supernatural? In the same essay, Pennock writes:

“Experimentation requires observation and control of the variables. We confirm causal laws by performing controlled experiments in which the purported independent variable is made to vary while all other factors are held constant and we observe the effect on the dependent variable. But by definition we have no control over supernatural entities or forces.”

.

The pursuit of data

Assumption are fundamental to understanding the usefulness of the outputs of a model. But the assumptions underlying the scientific method will also influence the data that we subsequently look for. This limitation has been noted by philosopher Karl Popper and historian of science Thomas Kuhn, who notes that the “route from theory to measurement can almost never be traveled backward”. Theories also tend to build on each other, usually without revisiting the underlying assumptions.

Popper examines this problem of nested assumptions in his critique of naturalism:

“I reject the naturalistic view: It is uncritical. Its upholders fail to notice that whenever they believe to have discovered a fact, they have only proposed a convention. Hence the convention is liable to turn into a dogma. This criticism of the naturalistic view applies not only to its criterion of meaning, but also to its idea of science, and consequently to its idea of empirical method.” (The Logic of Scientific Discovery)

Note again the emphasis (in the second sentence) on the problem of confusing model confirmation with verification. This self-reinforcement of theory dominates most of science. Kuhn writes:

“Once it has been adopted by a profession … no theory is recognized to be testable by any quantitative tests that it has not already passed.” (The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)

We will never find what we do not seek and are unwilling to see.

We will never find what we do not seek and are unwilling to see.

.

The usefulness of models

In their correct place, of course, models are very useful. The great French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace used Newton’s model of gravity to calculate the motion of the heavens (as well as for predicting ballistics) in his masterpiece Mécanique céleste. Napoleon asked to see the manuscript, being greatly interested in ballistics. According to the story, after perusing the equations Napoleon turned to Laplace and asked, “Where is God in your book?” To which Laplace famously replied, “Je n’avais pas besoin de cette hypothèse-là.” (“I had no need of that hypothesis.”).

Laplace was perfectly correct. He was using calculus to predict the motions of celestial bodies and bodies moving through air, and it is not useful to incorporate theological complications into that prediction. Remember: as simple as possible, but no simpler. Of course, Laplace also didn’t include gravitational attraction from other stars in calculating the orbits of the planets. In the real world, we believe that other stars do exert gravitational attraction, but it is a useful simplification in our model that we ignore them at the scale of our solar system.

Laplace’s model does not correspond perfectly to reality, but it does allow us to make sense of data and make predictions, provided that we stay within the limits of its assumptions. Popper comments on the usefulness of the Darwinian evolutionary synthesis, despite the great limitations of that theory:

“Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory, but a metaphysical research program … And yet, the theory is invaluable. I do not see how, without it, our knowledge could have grown as it has done since Darwin … Although it is metaphysical, it sheds much light upon very concrete and very practical researches … it suggests the existence of a mechanism of adaptation, and it allows us even to study in detail the mechanism at work.”

But let us never confuse useful with true.

.

Science and truth

So what can science really tell us, if not truth? Well, within the limitations of its assumptions, it can give us great insight into process and the nature of the material universe. But it cannot, by definition, tell us anything about the immaterial: including the supernatural, philosophical reasoning and morality.

The great Stephen Jay Gould, in his essay Nonmoral Nature, commented thus on the limitations of science:

“Our failure to discern a universal good does not record any lack of insight or ingenuity, but merely demonstrates that nature contains no moral messages framed in human terms. Morality is a subject for philosophers, theologians … indeed for all thinking people. The answers will not be read passively from nature; they do not, and cannot, arise from the data of science. The factual state of the world does not teach us how we, with our powers for good and evil, should alter or preserve it in the most ethical manner.”

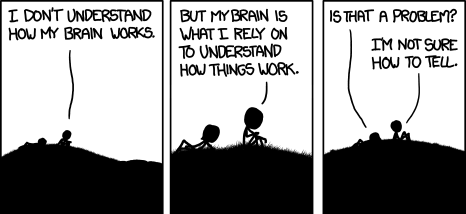

Indeed, science cannot even comment on the validity of its own assumptions: they must simply be accepted at face value for any science to be done at all. As per Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, they are postulates which cannot be proven by the system itself.

In our search for insight into the supernatural, we’re out of the territory of science. And recall the fundamental principle of modelling: we cannot change our objectives without re-evaluating our assumptions. So we can’t even adapt any current science to deal with these questions: science is simply not equipped for the task.

I do not propose allowing supernatural explanations into science. But I do suggest that it is very misleading to imply that science in any way supports a materialist worldview. This is mere question-begging: scientific theory, by its very assumptions, operates within a materialist worldview.

But we do not live in “science”. We live in reality.

Are we searching for truth, or are we searching for a theory nested in unprovable assumptions?

If the supernatural exists, it is beyond the tools of science. But if we have a supernatural aspect to our existence, it is not beyond our experience. To limit ourselves wholly to a materialist view may deprive us of fully experiencing a part of ourselves.

Philosopher Alvin Plantinga argues strongly for this line of thinking. He wrote:

“If you exclude the supernatural from science, then if the world or some phenomena within it are supernaturally caused – as most of the world’s people believe – you won’t be able to reach that truth scientifically.”

Are you missing out on something important by clinging to rigid materialism, perhaps because of a mistaken belief that such a worldview has scientific justification? Is there anything more to life?

Not to science. To life.

C. S. Lewis, certainly, had no doubt about the importance of our supernatural aspect. In Mere Christianity he described the human condition thus:

“You don’t have a soul. You are a soul. You have a body.”

What are you missing out on?

.

—————————————

Related posts:

On Spherical Cows and the Search for Truth (Part I)

Faith: reflecting on evidence

Believing and understanding

.

Note that Gould doesn’t simply say that the two fields are independent: he specifically says that they “bump right up against each other, interdigitating in wondrously complex ways along their joint border.” Of course, such a complex border would appear to be merely fuzzy from a distance, but it is exactly this interdigitation that we must explore. What Gould claims is that within every issue, whether moral or scientific, there are complex details which will fall into the domain of one or other field.

Note that Gould doesn’t simply say that the two fields are independent: he specifically says that they “bump right up against each other, interdigitating in wondrously complex ways along their joint border.” Of course, such a complex border would appear to be merely fuzzy from a distance, but it is exactly this interdigitation that we must explore. What Gould claims is that within every issue, whether moral or scientific, there are complex details which will fall into the domain of one or other field.