This essay is part of a series which explores historical encounters which are often presented as “conflicts” between science and Christianity.

Update:

This article has been expanded – the full version can be found here.

—————————————

“We have no sympathy with those who object to any facts or alleged facts in nature, or to any inference logically deduced from them, because they believe them to contradict what it appears to them is taught by Revelation.” (Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, The Quarterly Review, July 1860)

Second only to the Galileo affair in the “conflict” mythos is the encounter between Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Henry Huxley on June 30, 1860. Frequently referred to as “the Wilberforce/Huxley debate”, this story seems to have all the elements of the postulated “conflict”:

Wilberforce was at the time Lord Bishop of Oxford.

Huxley is best known for his aggressive defence of science (as reflected in his nickname “Darwin’s bulldog”) and his agnosticism (he in fact coined the term to describe his beliefs).

Darwinian evolution (and its perceived conflict with the Bible) is probably the most prominent battleground in the supposed “war” between science and religion. This incident took place the year after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species.

- The drama of the legend itself:

Here’s a typical account of the events (taken from Ruth Moore’s Charles Darwin, 1957):

“For half an hour the Bishop spoke, savagely ridiculing Darwin and Huxley, and then he turned to Huxley, who sat with him on the platform. In tones icy with sarcasm he put his famous question: was it through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed descent from an ape?

The cheers rolled up and the ladies fluttered their white handkerchiefs. Henslow pounded for order. The Bishop had scored.

At the Bishop’s question, Huxley had clapped the knee of the surprised scientist beside him and whispered, “The Lord hath delivered him unto mine hands.” The “wildcat” in Huxley was thoroughly aroused by what he considered the Bishop’s insolence and ignorance, and he tore into the arguments that Wilberforce had used… Working up to his climax, he shouted that he would feel no shame in having an ape as an ancestor, but that he would be ashamed of a brilliant man who plunged into scientific questions of which he knew nothing. In effect Huxley said that he would prefer an ape to the Bishop as an ancestor, and the crowd had no doubt of his meaning.

The room dissolved into an uproar. Men jumped to their feet, shouting at this direct insult to the clergy. Lady Brewster fainted. Admiral Fitzroy, the former Captain of the Beagle, waved a Bible aloft, shouting over the tumult that it, rather than the viper he had harbored in his ship, was the true and unimpeachable authority. Arguments broke out all over the room, and Hooker said that his blood boiled…

The issue had been joined. From that hour on, the quarrel over the elemental issue that the world believed was involved, science versus religion, was to rage unabated.”

What a story! The witty gibes, an ignorant clergyman talking out of his field of expertise, the iconic image of the Admiral dramatically waving his Bible, the ironic semi-ecclesiastical quip from Huxley as he rises nobly to meet this challenge to truth, the swooning ladies…

Pity it’s not true.

The image conjured above of rousing rhetoric from Huxley followed by descent into chaos and disorder is grossly misleading, as is the impression that Huxley was considered to have “won” the debate. This perception is based on thoroughly revisionist reconstructions, first by Huxley himself (over 30 years later) and then by 20th-century writers, largely due to shifting attitudes towards evolution and anachronistic re-interpretation of the actual events.

As Sheridan Gilley writes:

“The standard account is a wholly one-sided effusion from the winning side, put together long after the event, uncritically copied from book to book, and shaped by the hagiographic conventions of Victorian life and letters.” (The Huxley-Wilberforce debate: A reconsideration, 1981)

Let’s see if we can sift some of the fact from the fiction.

.

Settling the account

There is no verbatim transcript of the meeting, but it was reported in three issues of The Athenaeum (30 June, 7 and 14 July 1860), and there also exist numerous letters from those present which allow us to reconstruct the events with considerable confidence.

Firstly, it was not a debate – it was a series of discussions following the presentation of a paper by John Draper on some of the social implications of Darwinism. Although the presentation itself was by all accounts long and boring, the subject was a significant one, and Darwinism had been very much in the public mind that week. (Two days earlier, Huxley had vigorously debated the subject with Richard Owen after the presentation of a paper by the botanist Charles Daubeny). Darwin’s theories were on everyone’s mind, and only illness prevented the man himself from attending. The meeting was chaired by John Stevens Henslow, Darwin’s former mentor from Cambridge, and after Draper’s presentation Henslow invited various people to speak in turn.

The image of Huxley rising valiantly to defend Darwinism is not, it must be said, entirely accurate. After Draper’s presentation, Henslow invited Huxley to comment (in his capacity as a leading proponent of Darwinism), but was rebuffed with a sarcastic retort. Only then did Henslow turn to Wilberforce to put across some of the main points at issue.

We’ll deal with Wilberforce’s actual arguments a little later. Let’s first finish our construction of the events.

Huxley’s ironic quip “The Lord hath delivered him unto mine hands” first appears more than thirty years later, and is almost certainly a later insertion to the story. Huxley’s own contemporary account, in a letter to Henry Dyster on September 9, 1860, makes no mention of this remark. But he did personally insert the detail into two much later accountsof the incident: in Francis Darwin’s 1892 biography of his father Charles, and in Leonard Huxley’s 1900 biography of his own father. Huxley had also, by this stage, adopted a vehemently anti-clerical stance which can hardly have failed to colour his later recollections.

More reliable accounts indicate that although Huxley did respond with the “monkey” retort, the remainder of his speech was unremarkable. Balfour Stewart, a prominent scientist and director of the Kew Observatory, wrote afterward that (in a letter to David Forbes on July 4 1860), “I think the Bishop had the best of it.” Joseph Dalton Hooker, Darwin’s friend and botanical mentor, noted in a letter to Darwin (dated July 2) that Huxley had been largely inaudible in the hall:

“Well, Sam Oxon got up and spouted for half an hour with inimitable spirit, ugliness and emptiness and unfairness … Huxley answered admirably and turned the tables, but he could not throw his voice over so large an assembly nor command the audience … he did not allude to Sam’s weak points nor put the matter in a form or way that carried the audience.”

It is likely that Hooker’s main point is accurate, that Huxley was not effective in speaking to the large audience. He was not yet an accomplished speaker and wrote afterward that he had been inspired as to the value of oration by what he witnessed in that meeting.

Next, Henslow called upon Admiral Robert FitzRoy, who had been Darwin’s captain and companion on the voyage of the Beagle twenty-five years earlier. FitzRoy denounced Darwin’s book and, “lifting an immense Bible first with both hands and afterwards with one hand over his head, solemnly implored the audience to believe God rather than man”. Although there is some resemblance to the legend, note that this actually happened with the Admiral speaking from the podium in a well-ordered room.

The last speaker of the day was Hooker. According to his own account, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce’s arguments: “Sam was shut up – had not one word to say in reply, and the meeting was dissolved forthwith”. Canon Farrar, a liberal clergyman who was present, wrote later:

“The speech which really left its mark scientifically on the meeting was the short one of Hooker… I should say that to fair minds, the intellectual impression left by the discussion was that the Bishop had stated some facts about the perpetuity of the species, but that no one had really contributed any valuable point to the opposite side except Hooker.”

Notably, there was no consensus amongst those present as to which side had “carried the day”. In fact, all three major participants felt they had had the best of the debate:

Wilberforce: “On Saturday Professor Henslow … called on me by name to address the Section on Darwin’s theory. So I could not escape and had quite a long fight with Huxley. I think I thoroughly beat him.”

Huxley: “[I was] the most popular man in Oxford for a full four & twenty hours afterwards.”

Hooker: “I have been congratulated and thanked by the blackest coats and whitest stocks in Oxford.”

.

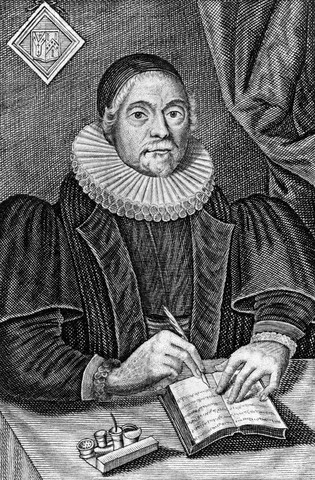

Wilberforce in context

Sam Wilberforce was not just the Bishop of Oxford, he was also a Fellow of the Royal Society, a prominent ornithologist and Vice President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. His part in the incident was not that of an ignorant cleric, but of a keen and accomplished amateur offering an important and considered critique of Darwin’s theory from a scientific perspective.

This is a vital point, because if we are to understand this incident at all we must rid ourselves of the idea that it was an exchange between religion and science. Indeed, it was for his knowledge of science (as well as his familiarity with speaking to large groups) that Henslow called on Wilberforce to comment.

Although we do not have a verbatim transcript of Wilberforce’s speech, the reports indicate that it was very similar in substance to a review of Darwin’s Origin of Species that he had penned just five weeks earlier (and published in The Quarterly Review of July 1860). Philosopher and mathematician John Lucas notes (in his essay Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter) that: “Wilberforce, contrary to the central tenet of the legend, did not prejudge the issue. The main bulk of the review is given over to an entirely scientific assessment of Darwin’s Theory.”

Let’s look at two key passages of Wilberforce’s review. In the first, we see a strong adherence to rational scientific principles and a dedication to following the evidence where it leads:

“But we are too loyal pupils of inductive philosophy to start back from any conclusion by reason of its strangeness. Newton’s patient philosophy taught him to find in the falling apple the law which governs the silent movements of the stars in their courses; and if Mr Darwin can with the same correctness of reasoning demonstrate to us our fungular descent, we shall dismiss our pride, and avow, with the characteristic humility of philosophy, our unsuspected cousinship with the mushrooms … only we shall ask leave to scrutinise carefully every step of the argument which has such an ending, and demur if at any point of it we are invited to substitute unlimited hypothesis for patient observation, or the spasmodic fluttering flight of fancy for the severe conclusions to which logical accuracy of reasoning has led the way.”

His point about consistent scrutiny of evolutionary theory has, sadly, been much overlooked in the last century, but more on that later. In another passage he unequivocally states his belief that scientific theories must be judged purely on their scientific merits:

“Our readers will not have failed to notice that we have objected to the views with which we are dealing solely on scientific grounds. We have done so from our fixed conviction that it is thus that the truth or falsehood of such arguments should be tried. We have no sympathy with those who object to any facts or alleged facts in nature, or to any inference logically deduced from them, because they believe them to contradict what it appears to them is taught by Revelation. We think that all such objections savour of a timidity which is really inconsistent with a firm and well-intrusted faith.”

We see very clearly here an intent to argue a scientific hypothesis from a scientific perspective, trying as much as possible to avoid pre-judging the results. Lucas comments further that: “On the strength of the review it would be quite impossible to make out Wilberforce as the prelatical apostle of ecclesiastical authority trying to down the honest observations of simple science.”

The report in The Athenaeum clearly indicates that Wilberforce presented his criticism of Darwinism from a scientific base:

“The Bishop of Oxford stated that the Darwinian theory, when tried by the principles of inductive science, broke down. The facts brought forward, did not warrant the theory…

Mr Darwin’s conclusions were an hypothesis, raised most unphilosophically to the dignity of a causal theory. He was glad to know that the greatest names in science were opposed to this theory, which he believed to be opposed to the interests of science and humanity.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal, the other publication to report on the meeting at the time, carried a similar description of Wilberforce’s arguments. Wilberforce, according to the Journal, condemned the Darwinian theory as:

“…unphilosophical; as founded, not on philosophical principles, but upon fancy, and he denied that one instance had been produced by Mr Darwin on the alleged change from one species to another had ever taken place [sic]. He alluded to the weight of authority that had been brought to bear against it – men of eminence, like Sir B. Brodie and Professor Owen, being opposed to it, and concluded, amid much cheering, by denouncing it as degrading to man, and as a theory founded upon fancy, instead of upon facts.”

.

The scientific case

So now that we have established that Wilberforce was arguing from science, what exactly were his arguments? Basically, he presented three points:

- In the timescale of human history, no evidence of the emergence of new species could be observed. This despite very long-term exercises in artificial selective breeding such as dogs and horses.

- While selective pressures did indeed seem to have an effect of causing changes in morphology (body type), they do not cause changes between species.

- The sterility of hybrids (such as mules, which are the offspring of horses and asses) argues strongly for the fixity of species and against successful changes in species.

Considering the actual arguments presented in Origins, and the state of knowledge at the time, these were all valid and highly problematic points against Darwin’s theory. Lucas clarifies:

“As regards the first point we now know that Wilberforce is wrong; but on the other two points he was right. Dogs, horses and pigeons have been selectively bred for thousands of generations, yet different breeds not only remain mutually fertile, but are liable to revert to type. Obvious changes in the phenotype are less significant than Darwin claimed, and species are genetically much more stable than he had supposed… Unless and until Darwinians could produce an explanation of how organisms of one species could eventually evolve into those of another, which also accounted for hybrid infertility and reversion to type, it was a fair criticism to say that Darwin had not offered a causal theory but only, at best, a hypothesis.”

Darwin himself regarded Wilberforce’s arguments as reasonable and fair. Writing to Hooker in July 1860, he said: “I have just read the Quarterly. It is uncommonly clever; it picks out with skill all the most conjectural parts, and brings forward well all the difficulties. It quizzes me quite splendidly.” On returning to work after his illness, Darwin immediately applied himself to the problematic areas raised by Wilberforce.

Darwin himself regarded Wilberforce’s arguments as reasonable and fair. Writing to Hooker in July 1860, he said: “I have just read the Quarterly. It is uncommonly clever; it picks out with skill all the most conjectural parts, and brings forward well all the difficulties. It quizzes me quite splendidly.” On returning to work after his illness, Darwin immediately applied himself to the problematic areas raised by Wilberforce.

Lucas further elaborates on the scientific strengths of Wilberforce’s arguments:

“In assessing Wilberforce’s argument, two crucial distinctions have to be borne in mind: first between the Darwinism that Darwin was propounding and what is understood as Darwinism today; and secondly between simple inductive generalization and an overall schema of explanation and interpretation. Evolution is not itself an immutable creed, but has itself evolved. The Neo- Darwinism that men of science now accept took its present form only in the 1940s and is at least three stages removed from the theory Darwin propounded. Darwin had no theory of genes and gave no account of how it was that species came into being: the very title of his book was itself a misnomer. What he was really arguing for was a hypothesis that each species had gradually developed from some simpler one, and the Survival of the Fittest as a partial explanation of how this had happened. Wilberforce claimed that the hypothesis was false and that the explanation failed to account for some crucial facts. In the review he devoted six pages to the absence in the geological record of any case of one species developing into another. Darwin had felt this to be a difficulty, and had explained it away by reason of the extreme imperfection of the geological record. Subsequent discoveries were soon to … fill in the stages whereby many different species had evolved from common ancestors: but in 1860 it was fair to point out the gaps in the evidence, and to argue that Darwin had put forward only a conjectural hypothesis, not a well-established theory.”

.

Conflicting stories

Returning to our “conflict” thesis, it should by now be clear that the 1860 meeting between Huxley and Wilberforce was not at all a clash between science and religion. It was certainly a heated discussion, but there are massive problems with the traditional tale.

- Not only was the meeting not a debate, Huxley by all accounts played a relatively minor role.

- The main substance of the debate was between Wilberforce and Hooker, with Huxley’s involvement limited to an emotional (but totally unscientific) series of verbal ripostes about apes and grandfathers.

- Everyone was at the meeting to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of Darwinism, not to debate any theological matters.

- Most importantly, Wilberforce debated his side from science.

As Lucas writes:

“…it is clear that [Wilberforce] did not argue that Darwin’s theory must be false because its implications for the nature of man were unacceptable. As he saw it, and as most of his audience saw it, he was showing that it was, as a matter of scientific fact false, and only having established this did he go on to say in effect ‘and a good thing too’.”

.

.

Additional Notes: Theory vs Paradigm

This issue of hypothesis vs theory vs paradigm is worth expanding on a bit, since we’re already buried deep in Darwinism. Wilberforce attacked Darwinism as a theory, and correctly pointed out that it was full of holes and the evidence didn’t really support it. But as Lucas explains, it won widespread support not as a theory but as a paradigm – that is, a schema of explanation and interpretation:

“Its immense appeal lay in its power of organizing the phenomena of natural history in a coherent and intelligible way. This was what had led Hooker to adopt it, and subsequently commended it, in spite of admitted difficulties and deficiencies, to almost all working biologists.

… Darwinism became at once a creed, to be espoused or eschewed with religious vehemence and enthusiasm. It was not just a Baconian hypothesis that could be accepted or rejected by a simple enumeration of instances independently of what was thought about other matters. Darwinism affected the whole of a biologist’s thinking, his way of classifying, his way of explaining, what he thought he could take for granted, what he would regard as problems needing further attention. We may take Huxley’s point that Darwin’s theory was not merely an hypothesis but an explanation.”

This status as a paradigm has two important implications. Firstly, Darwinism is held to be immune to conventional falsification. Secondly, as a broad philosophical framework in which biology operates, its must have near-universal acceptance for it to be useful. This explains much of the religious zeal with which the Darwinian creed is promoted. Furthermore, by describing a framework within which to think, there is a high risk that a Darwinian outlook will affect an individual’s entire worldview.

Ironically, despite the fact that he explicitly attacked Darwinism as a scientific theory, it may have been its status as a paradigm which concerned Wilberforce more: he anticipated the disastrous effects which Darwinist thinking could wreak if misapplied to social situations. In his review he refers to a section of Origins dealing with ants, and writes:

“…we detect one of those hints by which Mr. Darwin indicates the application of his system from the lower animals to man himself, when he dwells so pointedly upon the fact that it is always the black ant which is enslaved by his other coloured and more fortunate brethren. ‘The slaves are black!’ We believe [it is Darwin’s opinion] that the tendency of the lighter-coloured races of mankind to prosecute the negro slave-trade was really a remains, in their more favoured condition, of the ‘extraordinary and odious instinct’ which had possessed them before they had been ‘improved by natural selection’…”

Lucas suggests these options:

“To put the argument briefly in the form of a dilemma: either Darwin’s theory was a simple hypothesis, in which case difficulties about hybrids and reversion to type were fair and at the time well-nigh conclusive arguments against it: or it was a grand interpretative schema, in which case counterintuitive consequences about the nature and dignity of man were relevant and cogent.”